Report from AIA AAJ Fall Conference 2018: Jersey City, NJ

Roundtable Session: Evidence-Based Design Approaches -

Mentally Ill Offenders: Who is “My Keeper”?

By: Jacob Matthias Kummer

Speakers:

- Laura Maiello-Reidy,

- Brett Firfer, Assoc. AIA,

- Richard Wener, PhD,

- Kevin Murrett, AIA,

- Elizabeth Ford, PhD.

The National Alliance on Mental Health estimates more than 2 million arrests in the US involve people with serious mental illnesses. Mental health and access to treatment is the number 1 challenge facing corrections today. Solutions need to coordinate appropriate treatment, and provide the right physical environment for those who require a secure setting but what should the new paradigm for serving mentally ill persons in contact with justice look like and what will it take to get there?

On Thursday November 13th a round-table of multi-disciplinary experts joined us in Jersey City to discuss the state of current affairs and explore evidence-based design approaches that can help divert mentally ill persons from jail and prisons.

Current Affairs: An Evolving Understanding of Mental Health

In early colonial times detention facilities housed the “mentally disordered” population in “inhumane and uncivilized” conditions. The mentally ill in jails and prisons is hardly a new problem.

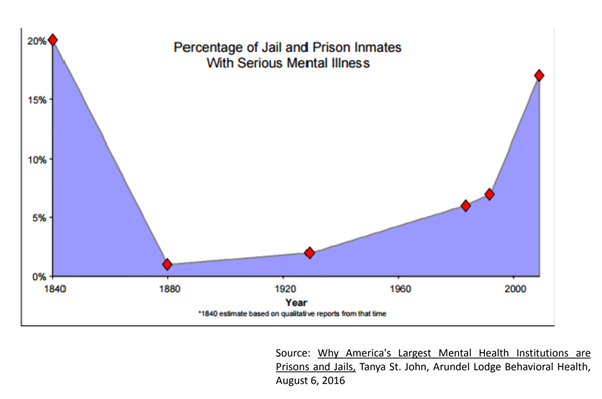

The early 19th century marked a change in the way the mentally ill were treated and detained. Advocates like Dorothea Dix argued there was no place in jails for the mentally ill and called upon states to fund the construction of psychiatric hospitals. After a vigorous program of lobbying state legislatures, the first generation of mental asylums was born in America. By 1880, 75 public psychiatric hospitals were in operation and mentally ill inmates were gradually transferred out of jails and into the state-run facilities. The proportion of prison and jail inmates with serious mental illness (SMI) rapidly decreased and continued to do so for the next hundred years.

“Prisons are not constructed in view of being converted into County Hospitals… And yet, in the face of justice and common sense, Wardens are by law compelled to receive and not to refuse [mentally ill] subjects in all stages of mental disease and privation”

Dorothea Dix, 1842

The Community Mental Health Centers Construction Act was passed in 1962. By this time the mental health hospitals had become overcrowded and isolated. This led to a transition from state-run mental health hospitals to federally-funded community mental health centers. These centers were to focus on prevention, early treatment and ongoing care closer to the patients’ home. This together with the discovery of antipsychotic medications and the introduction of federally-run health insurance programs gradually led to an emptying of psychiatric hospitals or “deinstitutionalization”.

Follow-up to treatment was often not carried out properly in the community mental health centers and many patients relapsed and committed offenses landing them back in the justice system. Once again jails and prisons started to be inundated with mentally ill offenders often without access to proper treatment. To this day jails and prisons are the leading provider of mental healthcare in the United States.

Finding alternatives to incarceration for mentally ill offenders is the number one challenge facing corrections today. Best practices need to be implemented at all stages of the judicial process including diffusing situations before leading to the arrest, treatment referral within the courts, dedicated spaces for the mentally ill in jails, and a greater focus in community reentry programs.

“Prisons are particularly good at being bad”: Increasing Knowledge based on Research and Empirical Study

Environmental conditions in our everyday life are proven to significantly affect levels of distress and depression. In prisons and jails there is no shortage of environmental stressors. Inmates have little to no control over stressful situations and can be exposed to multiple stressors at once and for extended periods of time.

Most of us on the “outside” have ways of coping with stress such as taking a walk around the block, smoking a cigarette or calling a friend. In prison or jail, coping mechanisms are largely unavailable. There is a lack of privacy, they are often overcrowded, and inmates can go through periods of severe isolation. Noise, lighting (too much or too little), lack of views or access to nature can have a significant impact on an inmate or staff’s well-being.

Exposure to these conditions can cause (and in some cases severe):

- Physical illness

- Reduced cognitive abilities

- Reduced ability to tolerate frustration

- Reduced helping behavior

- Increased irritability,

- Increased depression

- Increased sleep problems

Whilst these conditions can be damaging to everyone this is especially the case for offenders suffering from mental illness. Jail and prison environments are often inhumane and not supportive of treatment. Prison staff are often scared of the unpredictable behavior of detainees. Correctional officers are not mental health professionals nor are jails and prisons set up as treatment facilities. Their number one mission of detention facilities is containment and control.

Focusing on How Design Environment Impacts People

There is a stigma attached to being a patient in a mental health hospital. Patients are not “crazy”, they just need a little extra help in a safe and relaxing environment where they can receive appropriate treatment. When designing environments for the mentally ill, not only do we need consider what's best for the patients but it also needs to serve the staff (correctional officers, clinicians, case managers) and visitors.

Architects and designers need to apply empathic design approaches in order to imagine what it's like to be mentally ill and confined in these facilities. Patients/inmates with mental health illness do not process information and sensations in the same way that someone in good mental health does. There are four aspects to mental health facility design that architects and designers should consider:

[A] Safety

Safety is at the forefront of any detention facility design. Environments must be designed to be durable, control weaponization, prevent self-injury, and support effective management of ligature risks.

Designers can access the following resources when it comes to designing safe mental health environments:

Veterans Administration Behavioral Health Design Guidelines (cfm.va.gov)

NYS Office of Mental Health Patient Safety Standards (omh.ny.gov)

Behavioral Health Facility Consulting LLC. Behavioral Health Design Guide (bhfcllc.com)

[B] Color

It's important to understand the psychological effects colors might have on an average person but this is especially important in the design of mental health facilities. Color palettes should be soothing and natural whilst textures and patterns should be controlled and not overwhelming. Cultural, regional and age appropriation of colors must also be considered. For example, in some tribal communities the color white can signify “death” whereas in other cultures it can signify “faith” and “purity”.

[C] Light

Lighting effects our mood, behavior, and sleeping patterns. While access to natural light is not always possible in detention facilities, it is possible to create a tailored artificial lighting intervention that can result in a better quality of life for both patients and caregivers.

[D] Sound

Noise disturbance increases irritability, decreases concentration, and can contribute to a poor sleep environment. Designers must implement best practices sound control and absorption. Aside from the noise generated from inmate activities, building systems such as alarm and mechanical systems must also be considered.

Moving into the Light: Mental Health Reform on Rikers Island

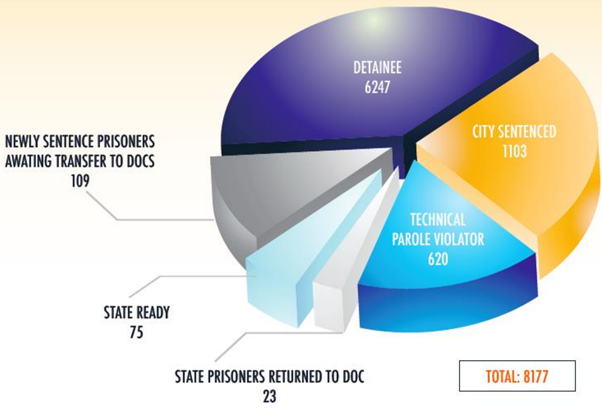

Rikers Island is a 400-acre island that is home to New York City’s main jail complex. The facility houses over 8000 offenders, around 40% of which require access to mental health treatment during incarceration. There is an ongoing evolution of mental health services on Rikers with particular emphasis on innovative, patient-centered and team-based care for individuals with serious mental illness.

NYC Department of Correction at a Glance. Information for entire FY 2018

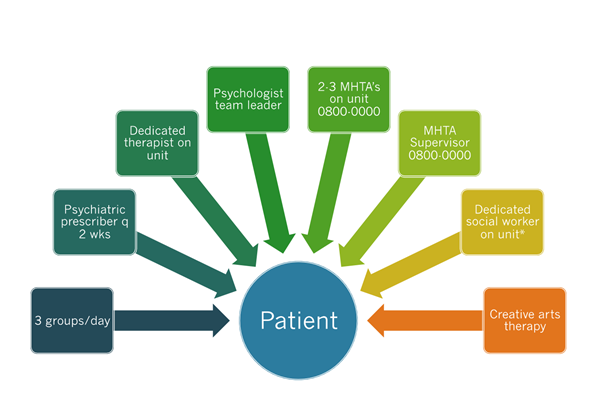

The Program for Accelerating Clinical Effectiveness (P.A.C.E.) forms part of the expansion of mental health services on Rikers. The program involves creating separate mental health units that will increase access to therapeutic interventions and improve the safety of officers and inmates alike.

P.A.C.E. Units integrate therapeutic design approaches to create an appropriate environment for treatment. Each unit incorporates:

- 18-35 bed units

- Therapeutic design principles (light, open space, offices on units, private individual therapy spaces, private group space)

- A specialized referral process

- Programming all day long

- Multi-disciplinary clinical staff (including nursing)

- Steady clinical and custody staff; team-based training and care

- Rewards and incentives for good behavior and treatment adherence.

The PACE Team Unit Model

Since the program began in Rikers Island in 2015, self-injury rates have been cut in half since, there has been a reduction in Uses of Force on Mental Health units, and on average there have been less than one suicide a year.

Jacob Matthias Kummer is an Architectural Designer at NORR in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.