Origins of Modernism: Critical Reconstruction

A question that all cities grapple with is what era of architectural heritage to honor and encourage. What are the guidelines to be – will future development look like something that’s come before?

Where I live in Charleston, South Carolina, this issue is ongoing and high-stakes; tourism is the city’s major industry besides shipping, and the reason for the tourism is the architecture. Sure, the architecture exists because of the sea and the port. But the architecture, dating from 1680, is breath-taking – wedding cakes houses, pastel stuccoed, multi-storied porches, narrow alleyways, quartz-lined sidewalks, neighborhood traditions that inspire famous musicals…Porgy & Bess, anyone? When the sun sets on Charleston, it sets on a city with centuries of grand architecture, and the city council has the burdensome task of maintaining design guidelines which are broad (overall height limits) and also specific (only round, metal gutters, thank you). Does the council encourage the architecture of a certain era, perhaps even a certain half-century among all the half-centuries that there have been? Which one? Who gets to choose? Who may feel excluded?

[forthcoming image of contrasting history in Charleston, SC]

The people and leaders of Berlin struggle with this choice, as well. Where construction or renovation occurs, what period of architecture is to be honored and encouraged? Or, what range of architectural styles or methods?

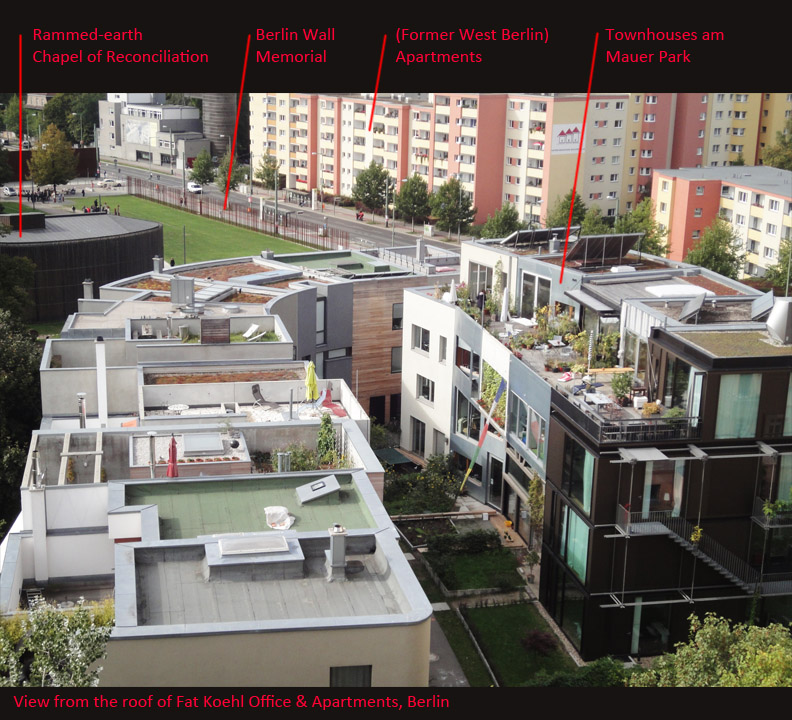

The image above shows the ever-present contrasts in the city: pink and yellow-painted West German apartment complexes which dominate the area, dating from sometime between the 1960’s and 1980’s; a permeable memorial to the Berlin Wall; a 2002 rammed-earth church honoring one there before East Germany came into being, and a new housing block, very modern, with a winding pedestrian pathway, differentiated facades for each building, and innovative use of materials – from within the past decade.

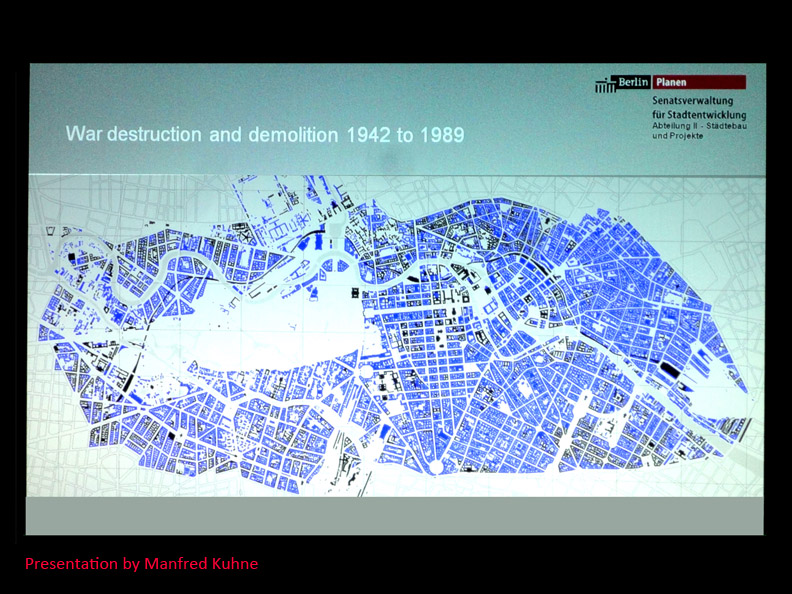

There has been much to rebuild in Berlin. Looking again at Manfred Kuhne’s graphic depiction of area available for redevelopment after 1989 – in blue – we see how extensive the area for redevelopment has been over the years.

As we heard from Mr. Kuhne, Department Head, Urban Design and Projects, Berlin Senate for Urban Development, Berlin, during the Origins of Modernism conference, “one of the benefits of the older building stock that was left after the destruction of World War II was that the remaining buildings mostly had a ‘lack of functional determinism’”, which meant that the buildings could be repurposed for many different types of use. This open-ended design means that buildings are contained by facades which do not necessarily show what goes on behind them – either in function or even in structural design. Late-Modern period buildings in particular use the structural systems of that era to that end.

Michele Caja in Italia World Magazine writes about the struggle:

“Can we still follow the model of the compact city of the history, in its different declinations from the Middle Ages to the baroque or its transformation in the XIX century, or do we have to remain loyal to the open schemata introduced by the Modern Movement up to their degeneration to the anti-urban models, where architecture is reduced to a spectacular object put inside a void without qualities?”

(http://www.arcduecitta.it/world/2013/02/critical-reconstruction-as-urban-principle-michele-caja/).

So, how to handle the enormous quantity of redevelopment throughout the city? How to make the best Berlin?

The current Berlin policy that answers this question is called ‘critical reconstruction.’ The idea, Kritische Rekonstruktion in German, was forwarded after 1989 by architect Josef Paul Kleihues (http://www.kleihues.de/, 1933-2004) as ‘careful urban renewal.’ It addresses architecture and city planning.

Critical Reconstruction regulations:

- A height limit of 72’-0” to a building’s cornice, or about 5 stories

- 100’ for the setback peak of a roof

- Individual buildings with identifiable entrances

- Streets lined with masonry-front buildings

- A return to traditional urbanism

- Building size limited to one block

- Mimics/refers to pre-World War I Berlin

“This was the Berlin version of an international trend: after decades of destroying the urban fabric, cities now sought to revive their endangered traditions of shared urbanity (p. 108).” “Critical reconstruction reaches back beyond world wars, dictatorships, and modern urban experiments and finds a Berlin identity in the decades before 1914, (p. 109)” that is, before World War I. These criteria are “intended to ensure that the sum of Berlin’s many construction projects is a lively and livable city (p. 231).”

Ladd, Brian. The Ghosts of Berlin: Confronting German history in the urban landscape. Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press.

One example of a design which meets these criteria is the remarkable and distinctive development on Caroline Von Humboldt Weg.

But the policy must be a challenge to implement. What parts of all of this architectural history of Berlin represent the best sides of the City? What era does the policy choose as the best side of Berlin? Is it the neo-classicism of the 19th and 18th centuries?

What about the more recent, 20th-century style of the former West Berlin?

And what about the important, playful history of Modernist architecture in Germany – that legacy is certainly one of the best parts of Berlin.

Few argue that it’s a good idea to replicate the cold, plain architecture of the former East Berlin and East Germany. When compared with the neoclassical structures found in the Gendarmenmarkt, the warmer buildings speak so much more fully to us about a meaningful existence.

Gary Wolf, a contributing writer with Wired Magazine, wrote about Critical Reconstruction in 1998:

“These planners discourage the aggregation of multiple lots into extended developments and require architects to follow strict rules governing the height and shape of the buildings, favoring stone and ceramic exteriors over steel and glass. Where possible, they want to restore prewar street patterns and building lines. “We are asking,” says Volke Hassemer, a former senator who now runs an influential city marketing group, “what was the role of the central city area in the 19th century? Then we must invent the contemporary equivalent.”

I heard some criticism of the program of critical reconstruction while in Germany, and have read some online. Primarily, the criticism is that encouraging masonry facades with underlying steel structures creates an empty style that tries to create an imagined, shared past, and does not promote modern architectural innovation.

Fortunately, for the attendees of the Origins of Modernism conference, we visited and learned about many examples which show an appreciation of new, ever-evolving design thought.